A Block 1 primatology class taught students how to put together formal research proposals, how to ensure accurate data collection, and how to appreciate non-human animals, all while traveling to the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo almost ten times! This six-person class allowed for an intimate class setting, where students not only learned the ins and outs of how to put together formal research proposals, but actually had the chance to create one, based upon research questions they formed at the zoo.

Krista Fish ’97, associate professor and chair of the Anthropology Department, taught AN306 Primatology, which she took as a student when she was at Colorado College.

During the first visits to the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo, students learned and practiced behavioral data collection methods. Students were taught the importance of being systematic when collecting data to ensure that they weren’t biased by attention-grabbing behaviors, such as infant play or a moment of aggression between two individuals, as those behaviors can then become over-represented in the understanding of primate behavior. Students were taught methods to minimize this type of bias.

Students used their experience at the zoo and their readings to come up with potential research questions and hypotheses. Throughout the second week of the class, students traveled back to the zoo to pilot methods to investigate their research questions. Students were then taught how to put together a formal research proposal based on those hypotheses.

During third week, Fish and her students traveled to the zoo every day for students to collect data. Due to the Block Plan, the time collecting data is limiting, as most behavioral data collection on wild primates takes place over the course of months or years, but the students were still able to experience the challenges of organizing and analyzing entire datasets, says Fish.

The week also allowed students who may want to continue with their research to have a sufficient sample size, to demonstrate that their project is feasible, which might allow them to be more competitive when pursuing funding for a longer-term project, says Fish.

The Block Plan allows the course to have an immersive field experience, which would not have been possible if students were taking more than one class at a time, says Fish. “Some years this class travels to a primate sanctuary in the United States, while in other years we conduct our research at the Cheyenne Mountain Zoo. Regardless of the location, students get the chance to spend a week collecting primate behavioral or ecological data for a project that they design.”

“I think only on the Block Plan can you go to the zoo with your class nine times in three and a half weeks! I could tell the students really got to know the primates they were studying and were able to collect hours of data for their research projects,” says Emma Ulbrich ’22, who was a paraprofessional for the class.

“I have loved getting to spend so much time at the zoo and getting to know my classmates. The beauty of such a small class is that everyone gets a ton of one-on-one attention from the professor and you get to know each other pretty well,” says Isabell Osborne ’23, an organismal biology and ecology major. “I know everyone in this class worked so hard on their research and final papers, and I'm so excited to read everyone's final product after the class ends.”

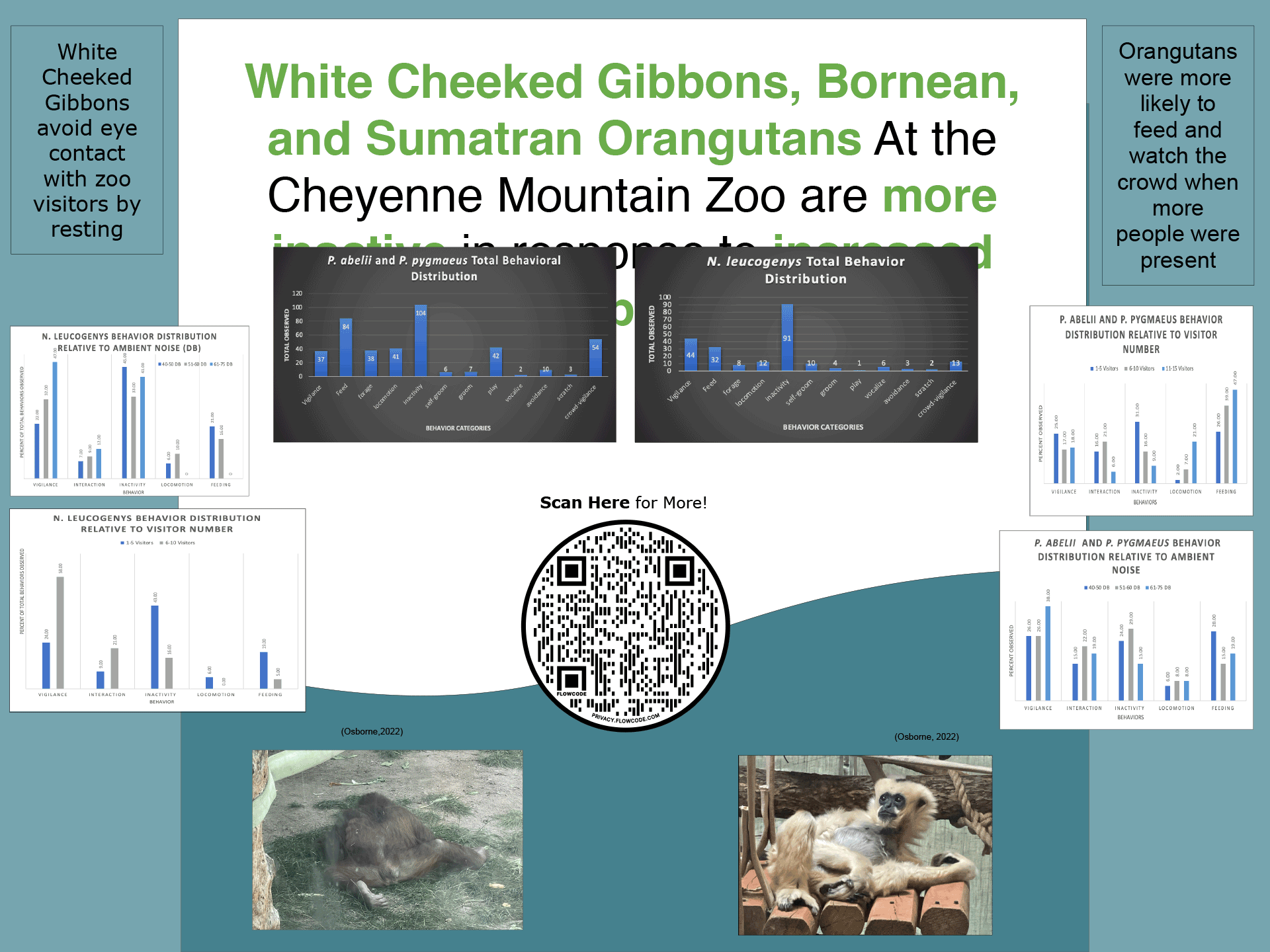

Osborne decided to take this course because she thought the focus on research would be invaluable as she looks towards graduate school. “I also just think primates are amazing! Who could complain about getting to go to the zoo every day for class,” added Osborne, who plans to pursue a Ph.D. in evolutionary biology. Osborne’s project was about the effect of visitor number and ambient noise on white-cheeked gibbon and orangutan behavior.

Fish hopes that students come away with more than primatology knowledge.

“I hope that students come away with an appreciation of what it means to do science — that it's often not the linear process that their textbooks outline. There are false starts and sometimes serendipitous events that alter what the students initially thought they were going to research,” says Fish. “Science is also creative and innovative, and I hope that they experience those parts of science as they carry out their project.”

Additionally, Fish hopes that her students leave her class with a deeper appreciation for non-human animals, particularly non-human primates.

“I hope that my students come to appreciate the different personalities of the primates they observe and that this informs their thinking about the ethics surrounding primate research, primate conservation, and the role of zoos in both research and conservation,” says Fish. “Finally, I also aim to get students thinking about the history of zoos as being bound up with colonialism and how that has impacted animal welfare and zoo visitors.”

“My favorite part of the course was the opportunity to design my own research question and methods of answering it – an opportunity that I had not had before. I learned a lot about the scientific process, and I gained confidence in my ability to do research in the future,” says Reeve Schroeder ’24, a student in the class.

Schroeder’s project focused on the interactions between captive western lowland gorillas and zoo visitors ages 12 and under.

While this is not the first time Fish taught this class, it is the first time she taught the class using “ungrading,” which is a practice Fish has been incorporating in her classes for the past four semesters.

Ungrading is a method focused on understanding the historical context around the grading system that’s been inherited over time, including how it was shaped by racism and sexism, analyzing how that grading system may interfere with student learning, and then taking steps to change the system, says Fish.

“I think that in all the classes where I have used ungrading, students report that it often removes anxiety, giving students room to try new things and ‘fail.’ This is important to the scientific process as not every idea we want to investigate will work out and give us interesting or exciting results. Students are much less focused on trying to get the ‘right’ answer (or the answer that they think I want) and are better able to focus on the process of doing science,” says Fish.

Schroeder said her advice for a student who is considering taking the class is to go for it.

“Dr. Fish is a fantastic professor, and the course is well designed for student success. Even if primate or animal behavior is not your main focus, you will be surprised by the ways in which you can connect your research to your other interests or areas of studies,” says Schroeder, who is a double major in anthropology and Hispanic studies.

Cheyenne Mountain Zoo was a Collaborative for Community Engagement partner about ten years ago, and Fish, along with the CCE, are working towards getting re-connected to the zoo for future classes.