| ‘Don’t Call Me Dad:’ Former Dean Glenn Brooks Explains Why He’s Not the Father of the Block Plan | |

| by Anne Christensen Photos courtesy of Tutt Library Special Collections |

The idea of one course at a time sounded “crazy,” but the small faculty group pursued it and its corollaries: residential life and extracurricular life.

In 1969, when political science Professor Glenn Brooks returned to Colorado College after a year of teaching in Kenya, President Lew Worner had an interesting assignment awaiting him. The college was six years away from its centennial, and Worner wanted Brooks to coordinate a “fresh look,” a campus-wide examination of both academics and life outside the classroom.

In 1969, when political science Professor Glenn Brooks returned to Colorado College after a year of teaching in Kenya, President Lew Worner had an interesting assignment awaiting him. The college was six years away from its centennial, and Worner wanted Brooks to coordinate a “fresh look,” a campus-wide examination of both academics and life outside the classroom.

“The Block Plan wasn’t in anyone’s mind,” says Brooks of that typically CC-style open assignment. As Brooks and a few other fresh-lookers began to talk with people, they heard repeatedly that most everyone liked the college’s commitment to liberal arts — this at a time when, says Brooks, “A lot of colleges were moving away from liberal arts to offer graduate programs, technical, and professional programs. They were worried about enrollment, but we never wavered from the liberal arts.”

However, says Brooks, they heard disturbing news from students about the conflicting demands of their classes and the need for more focus and balance in their lives. “I was ice skating with Nicki Steele ’69 one day, and she told me, ‘I had to cut one class one day to work on a paper for another class. I feel torn apart,’” Brooks recalls. “Students felt chopped up!”

That fall, the idea of more focused learning began to take shape. At a now-famous meeting at Murphy’s Bar, professors Tim Fuller, Doug Freed, Don Shearn, David Finley, and Brooks compared notes on the widespread frustration they’d found and discussed how they could do a better job. Suddenly Shearn burst out, “Why can’t the college give me 15 students and let me work just with them?!”

If there was a single moment of birth of the Block Plan, says Brooks, that was it.

The group at Murphy’s discussed how it could be done. Brooks remembers that the idea of one course at a time sounded “crazy,” but they pursued it and its corollaries: residential life and extracurricular life.

“Change was in the air, and there was a radical spirit in education,” says Brooks. In late 1968, Brooks got the go-ahead from Worner and Dean George Drake to form a plan, and that spring, they shifted into a planning phase. Initial faculty reaction was “puzzled, interested, and mostly receptive to change,” says Brooks, although some adamantly denied its potential. “You can’t teach physical chemistry in one block,” one professor stated flatly.

“P-chem became our poster child,” says Brooks — the measuring stick his group used as they discussed how semester teaching could be re-formed into blocks.

That summer, a fluid mix of people began to investigate the possibilities of this enormous design change. “The college was a committee of the whole,” says Brooks. “Lots of different people were involved at lots of different times — students, faculty, staff, and others.”

| “ | Students led the way.” |

| – Glenn Brooks |

More students then tried to create their four-year schedules out of those departmental sequences. Meanwhile, Brooks worked with faculty members, starting with the science departments. “What could you do off campus?” he asked them. “Field trips for geology? Biology? Anthropology?” Soon, he says, “The foreign language people began to perk up too.”

Brooks credits the rapid spread of interest to “the pre-existing open, flexible culture of CC.” Faculty reaction was mixed initially, but student reaction was mostly positive. “Students at other institutions were occupying buildings, but here they sensed the possibility for open-ended work toward change.”

Brooks’ still-varying group began detailed discussions of The Colorado College Plan — all three legs: residential life, leisure programs, and the Block Plan for academics. They identified advantages: “Greater freedom for faculty; greater freedom for students to learn in fresh and focused ways; greater opportunity to take advantage of our location and environment, especially for science, but also humanities and social science; more intimate and intense interchange between students and faculty; more flexibility of hours. Then we realized that we could fit into others’ programs — our students could participate in other institutions’ semesters abroad, fit into other institutions’ calendars.”

However, the group also realized that the Block Plan itself presented challenges, especially in subject areas like math, chemistry, and economics. “That’s a fair point, and an empirical question we have continued to test,” says Brooks now.

|

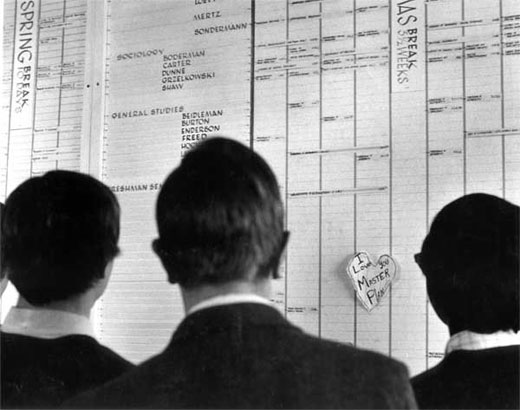

| CC students study the 1970-71 class schedule on one of four 8-foot panels in Rastall Student Center. |

| Photo by Ben Benschneider |

“The Academic Program Committee took on a strong role too, dealing with the more difficult technical issues. We had to prove there were enough classrooms if we used lounges and other unused areas. (The late) Malcolm Ware ’69, Jim Levison ’73, and David Struthers ’75 raided the Salvation Army for furniture to set up the ‘new’ rooms. The students had a real sense of ownership.”

In late October, the Academic Program Committee scheduled a faculty vote on the proposal. Debate was “hot and heavy.” While Worner had maintained “Olympic neutrality,” says Brooks, Drake expected it to pass, which it did by 58 percent. Immediately, President Worner said, “It’s been approved; what does that mean?” Professor Ray Werner, who had opposed it, answered, “It’s been a fair fight; I move we implement the plan.”

| “ | Students at other institutions were occupying buildings, but here they sensed the possibility for open-ended work toward change.” |

| – Glenn Brooks |

Logistically, Brooks said, students led the way again, by setting up a mock preregistration day on the quad. “It was a terrific way to educate students on what was coming, and detect some flaws in the system before we really started,” says Brooks. After that point, the registrar’s office got deeply involved. “It was all hands on deck from then on. Most of us had to figure out fresh teaching methods on our own. No consultants were available, because we were leading the way on this!”

|

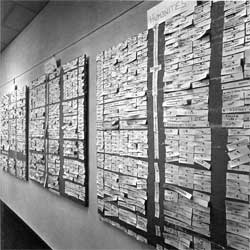

| In 1969, departments (more or less willingly) came up with possible course schedules under the Block Plan. Courses listed above include Russian History, Sculpture, Islam, History of Ancient Philosophy (with a field trip to Athens), and a seminar on Elizabeth Barrett Browning. |

“That’s the question I’m asked the most,” says Brooks. “‘How did you persuade faculty to vote itself more classes?’ It took the mood of the times plus a core of special faculty members who were very dedicated to liberal arts and sciences and this institution, and who were willing to try something new. There was a core of young Turks on the faculty: Dave Finley, Don Shearn, Tim Fuller, who came in the Benezet years, who were young and frisky. And there was my merry band of students in the planning office!”

So what did CC gain and lose by implementing the Block Plan? “We gave up bumping into each other around campus (between multiple classes) — the social function of academics was lost, although extracurricular and residential life picked up. And faculty members don’t see the same students over as long a period of time. We lost frequency, despite our premise that the Block Plan would increase contact.”

However, says Brooks, the Block Plan has fulfilled every goal its planners set, from intense focus and intimate instruction to making it easier for students to take prerequisites later and change majors later in their college careers.

|

| If you can identify the 1974 occasion or the students walking around campus in the block, please write the Bulletin at lellis@ColoradoCollege.edu. |

The Block Plan brought pleasant surprises as well, Brooks says. “Faculty and students have created new opportunities. Block breaks were not clearly envisioned, but we thought they’d be chances for seminars on poetry or current events. Instead, students take to the hills! They work intensely, then really take breaks. And there has been a lot of evolution in our use of off-campus sites.”

Brooks clearly relishes the planning and implementation of The Colorado College Plan as much as he did 35 years ago. “Initially, I had a full teaching load while I worked on this. All of us did it out of our hip pockets. ‘Father of the Block Plan’ doesn’t fit well,” he says. “I was the bagman, planning and politicking. I’m good at working with a lot of people, listening, trying to understand their hopes and worries, and building them into a workable plan. There were a lot of people involved who were willing to try, who made it work.”

And that’s the origin of the Block Plan, from its original “bagman” — not its father.