| Professor, Students Land BIG Dinosaur Evidence | |

| By Jennifer Kulier Photos by Tom Kimmell |

|

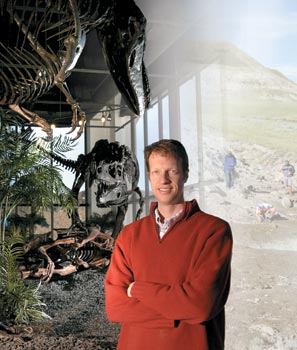

| Geology Professor Henry Fricke visits some old friends — some really old friends — at the Rocky Mountain Dinosaur Resource Center in Woodland Park, Colo. |

The same goes for dinosaurs.

Geology Professor Henry Fricke and his CC students are putting into practice that well-used dictum and uncovering important information about the way dinosaurs lived and moved through the landscape 65 to 75 million years ago.

Every summer, Fricke takes five or six students — a combination of first-years, sophomores, juniors, and seniors — to locations in North Dakota, Utah, or Montana to collect fossilized remains of dinosaurs that lived near an ancient seaway that ran from Mexico to Alaska.

The research they do takes advantage of the fact that the carbon chemistry of a plant is different depending on local conditions — arid or wet climate, dense forest canopy or open grassland. The chemical makeup of oxygen in river and lake water also varies. Thus, when a dinosaur ate the local vegetation and drank the water, their special chemistry was passed on in the animal’s tooth enamel, leaving a geochemical record from which researchers can infer what the dinosaurs were eating and drinking.

Fricke and the students grind the enamel off the dinosaur teeth, send it off to a lab for chemical analysis, and then interpret the data.

Just Your Average Dinosaur- hunting Day on the Block Plan

First there’s the highway driving — getting from Colorado Springs to a remote part of North Dakota or Montana. Then comes the dirt-road driving, sometimes for 50 miles or more, on Bureau of Land Management land.

When they finally reach their destination, the party sets up camp close to where they’ll be prospecting, generally near a river or creek bed. Other researchers have already identified these areas as rich in fossils. Surviving a one- to two-week dinosaur expedition requires not just an inquisitive nature, but a hardy one too. Everyone sleeps on the ground or in tents, cooks their own food, and uses nature’s own “facilities.”

The next day, the party sets out on foot to the fossil-producing outcrop where the area’s history is revealed on a steep slope containing layers of remains of former residents. Walking slowly along, eyes cast downward, the prospectors search the ground for teeth and bone fragments that have washed out of the slope during spring and summer rains.

For the first couple of days in the field, Fricke teaches the students to identify the ancient animal remains. The fossil fragments they find don’t always belong to dinosaurs; they might be a piece of turtle shell or a crocodile tooth, so it’s important for the students to know what they’re looking at.

Prospecting can last for four hours or all day, depending on how rich a site is.

It truly is a treasure hunt, says Fricke. “Sometimes you can walk around for hours and not find much. If you find a nice big tooth, it can make your day!”

The geochemical data they have collected provides the first solid evidence that different types of dinosaurs ate different types of plants, rather than competing with each other for the same food — a concept called “niche partitioning.” They have also found evidence that indicates dinosaurs tended to stay in one area, rather than migrating long distances as some scientists have posited.

In the long run, Fricke, his students, and other researchers hope to create a geographic database that will allow them to look at patterns in dinosaur geochemistry across a broad swath of North America.

Interestingly, Fricke and his students are finding evidence that the more well-known dinosaur researchers — paleontologists — can’t uncover on their own.

“Traditional paleontologists infer a great deal from the shape and relation between different bones, and so they are most excited to find complete dinosaur skeletons. However, complete skeletons don’t help us much,” Fricke said. “With one skeleton, you might have 50 teeth, but they’re all from one individual. We’re looking for isolated teeth from a larger number of individuals that get collected in deposits, because it tells you more about a population of organisms. That’s worked out well because our work complements the paleontologists’; I don’t require anything valuable so I can use their scraps.”

While Fricke says the first-year and sophomore students act as field assistants and “get to see some rocks and see what geologists do,” juniors and seniors have more hands-on involvement in the research, collecting samples, interpreting the results of chemical analysis, and sometimes writing theses or having the option to present the research at a national conference.

The National Science Foundation and the American Chemical Society Petroleum Research Fund help support Fricke’s research.

|

| Back at the CC geology lab, students check out fossil finds from their field work. |