Classes Emphasize Multicultural Works

By VICTOR GRETO '87

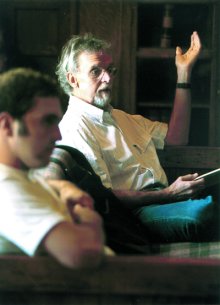

nglish Professor Dan Tynan is always nervous on the first day of class. Twenty-eight years of teaching at Colorado College haven't altered the first-day jitters.

First of all, Colorado College's peculiar Block Plan demands intensity: Nearly a month of daily three-hour classes on one subject requires your full attention.

And this block, he's teaching a class that covers a lot of material in a short period: the 20th-century novel. The choices of what to include are daunting.

There are 11 students the first day. Others beg to get into the class even if they don't satisfy the requirements, which include a class on literary theory. Tynan won't let them. Nothing beats a small class for lively discussion, he says.

The first question a student posed is perhaps the most obvious: Why did you pick these books to represent the 20th century?

The question of the "literary canon" has both plagued and revolutionized college teaching in the past three decades. Since the 1960s, ethnic groups have increasingly argued for inclusion into what was considered the "canon:" work that has been accepted as "great literature" and taught at both high schools and colleges in required classes. These classes included such stalwarts as Shakespeare, Wordsworth, Dickens, Chaucer and Joyce. People have often taken traditional sides over the issue. "Conservatives," including prominent Yale Professor Harold Bloom, argue that a world without Shakespeare is a barren world indeed. Multiculturalists say the literature that came from other ethnic groups' experiences in the United States is equally important and should be included alongside the accepted "great books."

The question of what to include in the canon also points to the very basis of a "liberal arts education": Question your assumptions. That goes for the books you pick as representative of a time period.

For his part, Tynan doesn't hesitate at the question.

"It's partially my training, partially my personal taste and partially the Block Plan," he tells the class. "I really don't like to teach books I don't like, and I more or less like these texts."

The first part of Tynan's book list includes authors James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, D.H. Lawrence and William Faulkner. Their books have been in 20th century novel classes for several decades.

The other authors on the list -- Thomas Pynchon, Toni Morrison and Alfredo Vea Jr. -- have as yet to stand the test of time, Tynan says. But the point, he says, is that they all have a quality that invites discussion.

On a sunny fall day, four Colorado College English professors gathered over lunch to talk about their trade. They included Tynan; John Simons, professor of English; Claire Garcia, associate professor of English; and Barry Sarchett, associate professor of English and chair of the department.

According to Sarchett, English teachers have three tasks: to teach students to read carefully, think critically and express themselves vigorously when responding to a text; to pick representative texts that are culturally inclusive; and to make literary judgments of which texts are the best.

The first may be the most important of all, but the problems posed by the questioning of the literary canon reside with the final two points.

As Sarchett describes it, a teacher must now choose from a larger number of texts from all ethnic groups.The growing number of texts that are now accepted means teachers must be both knowledgeable about a lot of other traditions and a good judge of the quality of the books.

And a judge of their students.

"When we have a student body that's primarily middle and upper class and whose parents have libraries full of [the classics]," Sarchett says of Colorado College, "I feel the duty to push them out of that and into other cultural trends."

U.S. News & World Report ranked Colorado College as one of the top 25 liberal arts schools in the country. The student body is also 86 percent white. How does the sameness of the school's white student body affect teaching? For Garcia, who teaches some black literature, the issue of race "is in the text, not in the composition of the (student) body."

The professors disagreed with the claim that literature is easier to understand if the reader has experienced something similar to what is told in the story or came from the same background of the author -- that one must be black, for example, to understand Toni Morrison or James Baldwin.

For both Tynan and Sarchett, the magic of literature lies in its power to communicate difference."If all you want to do is hold a mirror up to yourself, then go home," Sarchett says. "I want encounter and difference."

Victor Greto, a Phi Beta Kappa who majored in English at CC, is a writer and editor at the Colorado Springs Gazette. The preceding article is reprinted with permission.

Back to Index